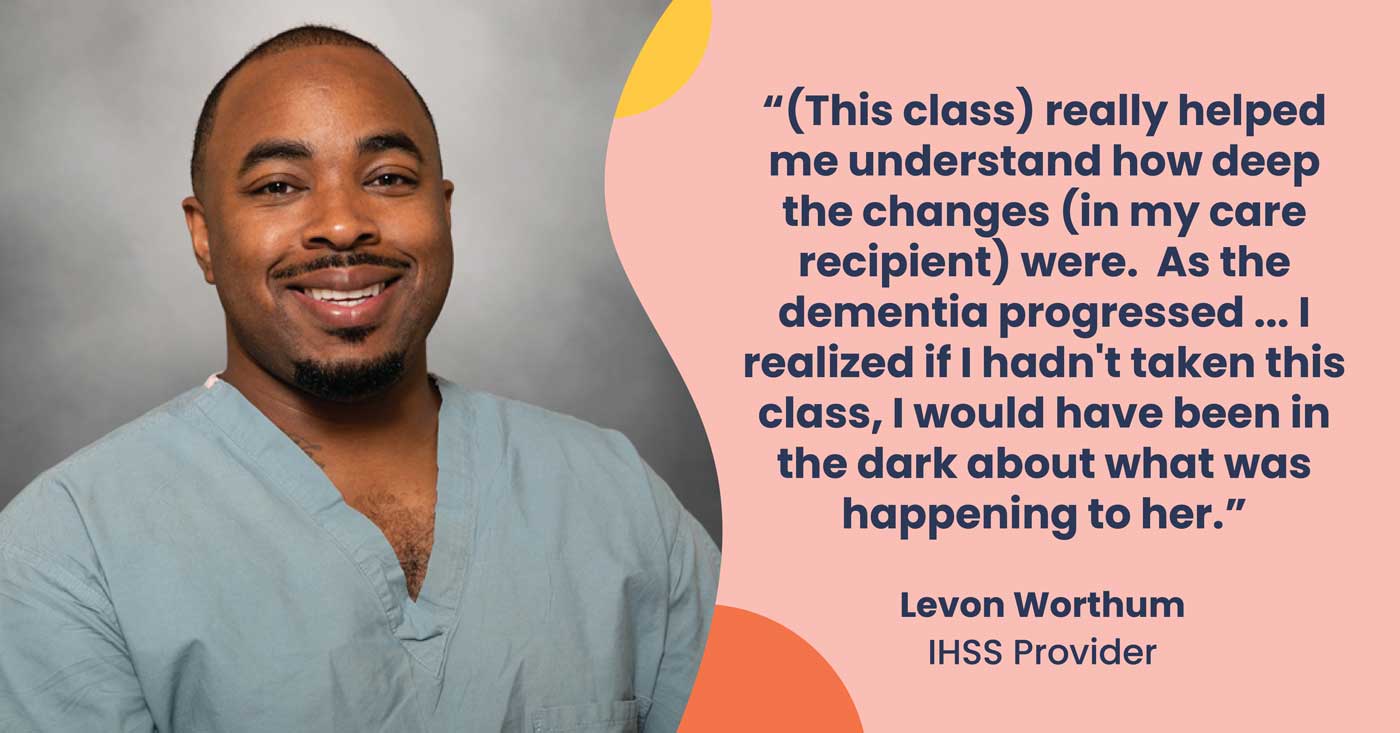

The signs were there, but caregiver Levon Wortham was in the dark about what to do. Then he signed up for a caregiver training program that focused on caring for seniors with Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia or cognitive decline.

“My Alzheimer’s class really did help me a lot because it allowed me to recognize a lot of the issues that I knew were there, but I didn’t have any definition or reason for them,” Levon says.

Levon is part of the first cohort of In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) caregivers to complete the Center for Caregiver Advancement’s IHSS+ Alzheimer’s training program in Alameda County.

“So just after taking this class, it really helped me understand how deep the changes (in my care recipient) were. As the dementia started to progress, I started to notice the signs of progression. I realized if I hadn’t taken this class, I would have been in the dark about what was happening to her,” Levon says. Trained caregivers like Levon are pivotal to helping people living with Alzheimer’s remain in their homes. Proper training ensures that the caregiver understands the disease, recognizes areas of concern, and can report to the care team, and knows strategies on how to provide better care.

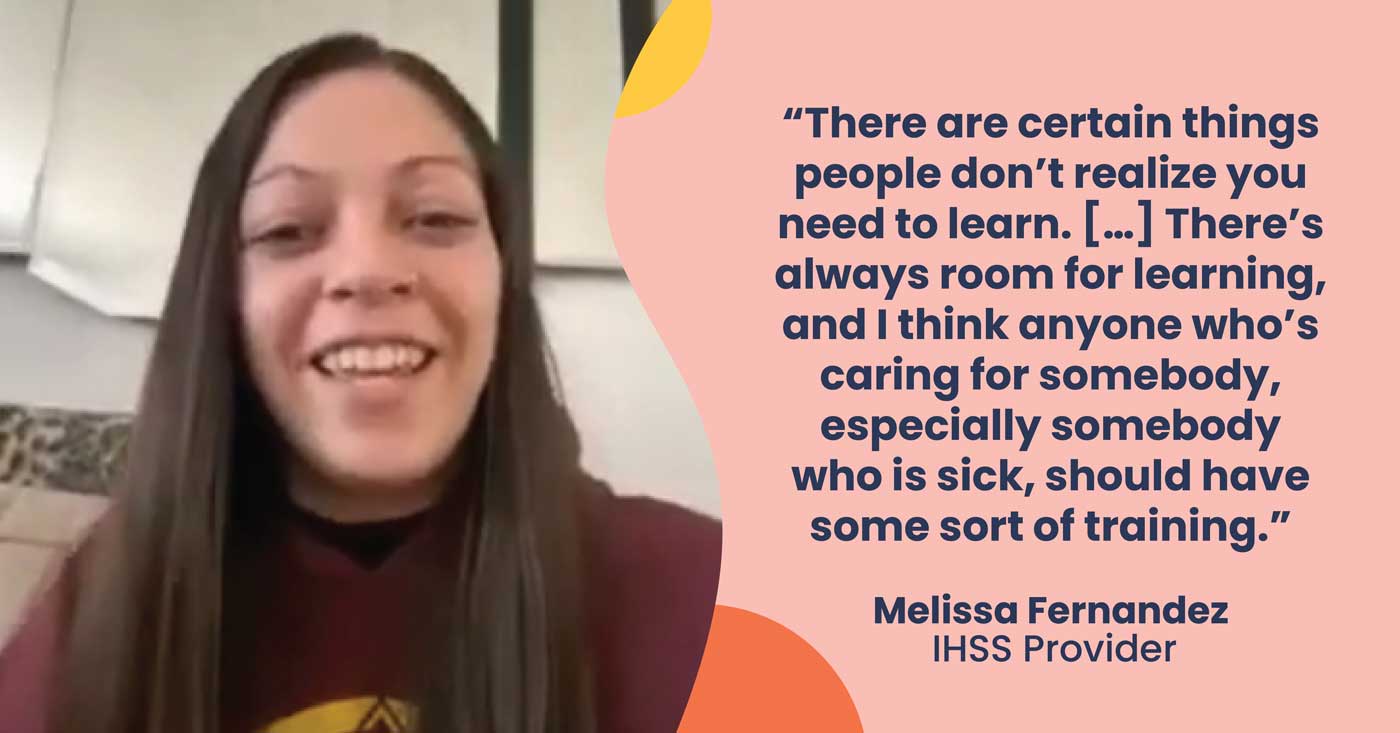

In California, there are over 520,000 IHSS providers caring for more than 650,000 elderly or people with disabilities in need of home care services. Often, these IHSS caregivers enter the workforce with little to no training or support.

“I go back to my notes from class a lot. And I continue to reflect on the different experiences and different topics we talked about in class. It’s really, really helpful,” says Levon.

The number of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias will double by 2060, according to a study from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. And among people 65 and older, African Americans have the highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s and dementia, followed by Hispanics, Native, and Asian populations. By 2060, researchers estimate there will be 5.4 million Black and Hispanic people living with the disease in the US. This reality calls for a much larger, more culturally competent workforce of caregivers with training on how to care for those with Alzheimer’s or other forms of cognitive decline. It will depend on trained caregivers like Levon.

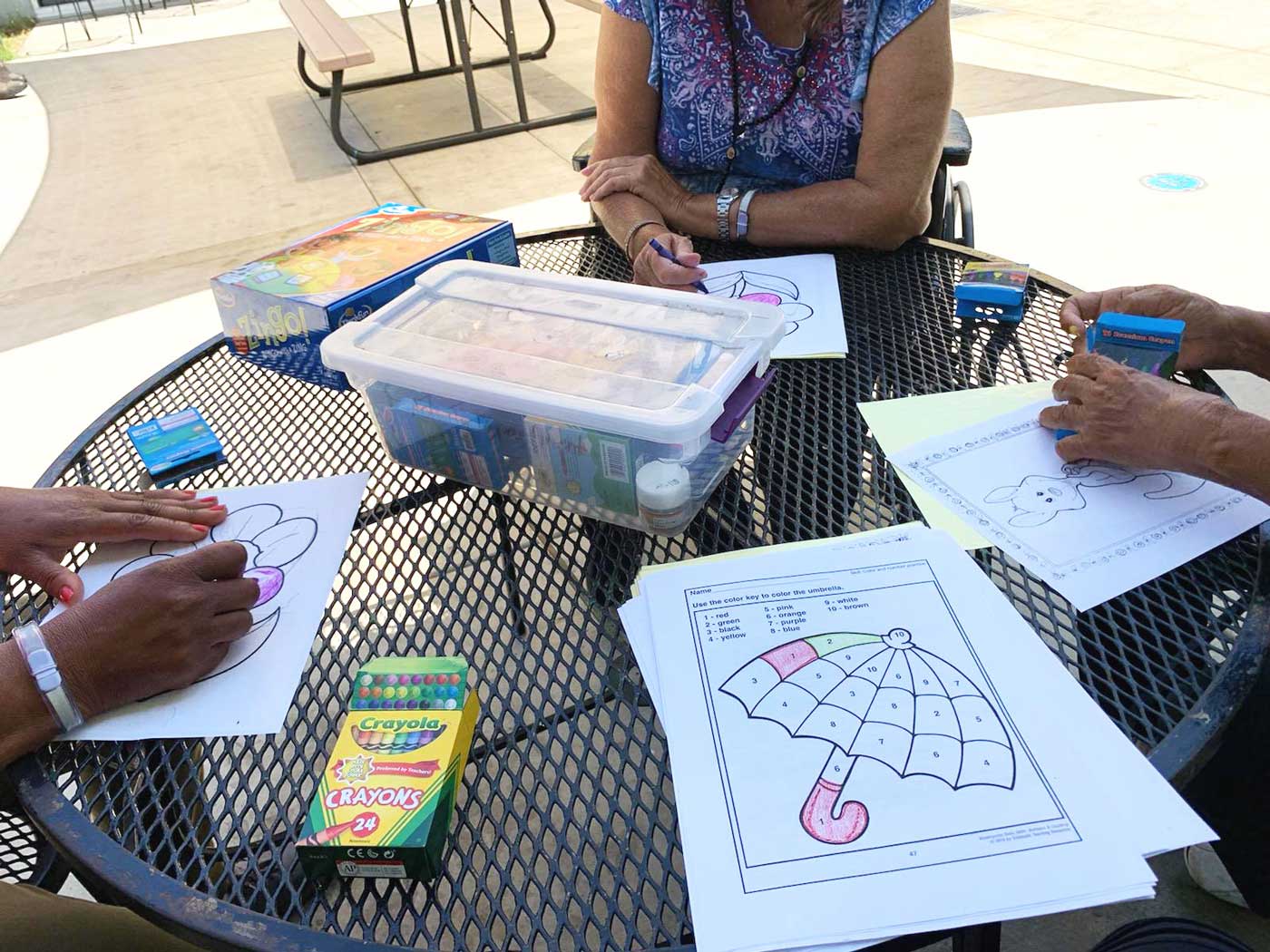

The biggest impact of the training, Levon says, was that it made him a stronger advocate for his consumer. The voluntary 10-week course teaches skills that are crucial to helping people who are showing symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Embedded in the curriculum are strategies for managing repetitive behaviors, assisting with daily activities such as bathing and medication, and helping to manage hallucinations and wandering.

Because he gained a deeper understanding of what she was experiencing, he adjusted how he was taking care of her. The training expanded his knowledge of the disease, which allowed him to recognize the symptoms and respond in a way that helped him connect with the consumer more effectively. And knowing the terminology and how to speak the language of the care team of doctors, nurses or personal support workers, helped him to become a better advocate.

“The most valuable lesson that I learned during my training, I would say, is just how to be an asset to the care team, because my experience or my witnessing (of the changes in my consumer), and my advocacy are very important,” he says.

Levon spends almost every day with his consumer, so he knows he can be a second pair of eyes when it comes to observing and monitoring her symptoms. He saw himself as a historian of sorts: He took detailed notes – reactions to medication, changes in behavior – and reported all of those to the doctors and the care team.

“I’ve actually had that response from the doctors that I communicate with that what I report is really helpful to them,” he says. “They think I’m just the smartest person on earth, but I’m really not! I’m just really paying attention and understanding how important it is to be able to relay these things to the doctor for my consumer.”

Backing up his instincts with actual data went a long way into making the care team take him seriously, and to recognize and respect his role as an IHSS caregiver as a critical component of the healthcare system.

“The most rewarding part is just knowing that what I’m doing is actually helping someone who, if I wasn’t doing this, would be going without care,” he says. The reward is in knowing that someone “feels that they are cared for.”

The IHSS+ Alzheimer’s training project in Alameda County is funded by the California Department of Health, in partnership with UC San Francisco and Alameda Alliance for Health.

Sources:

Government of California. “California Master Plan For Aging: Caregiving That Works” Master Plan For Aging, 2019, mpa.aging.ca.gov/Goals/4.

“U.S. Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease, Related Dementias to Double by 2060 | CDC Online Newsroom | CDC.” Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 Sept. 2018, www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0920-alzheimers-burden-double2060.html#:%7E:text=Among%20people%20ages%2065%20and,Pacific%20Islanders%20(8.4%20percent).