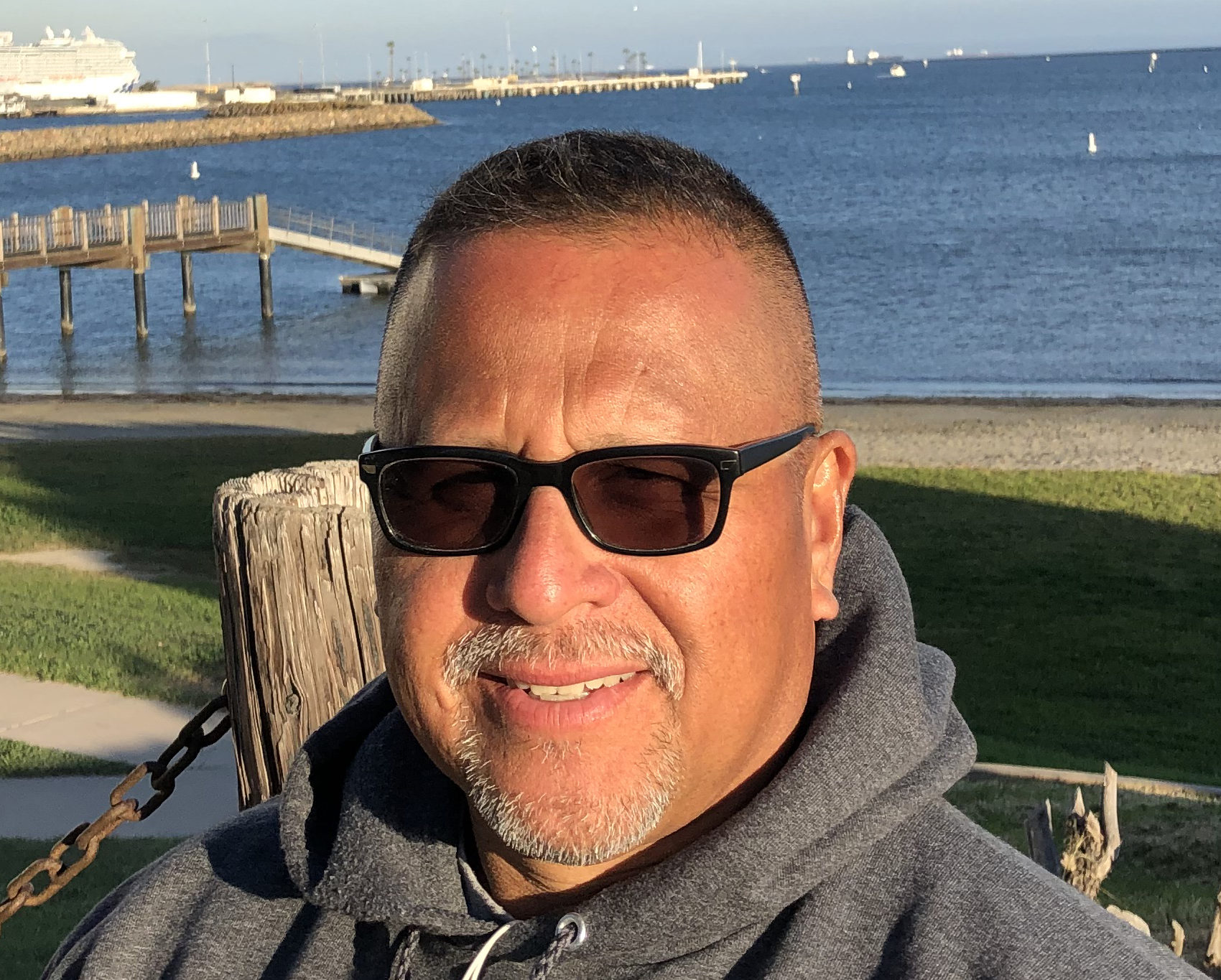

In his mind, Carlos Corona has two mothers. One is of the past, the mother who was vibrant and energetic and could do everything. The other sits across from him today, unable to recognize her oldest son due to Alzheimer’s disease.

“Once in a while, you look out of the corner of your eye, and think, those two pictures don’t go together,” he said. “And then you have to come back (to reality). Now it’s easier and faster for me to come back from those brief moments.”

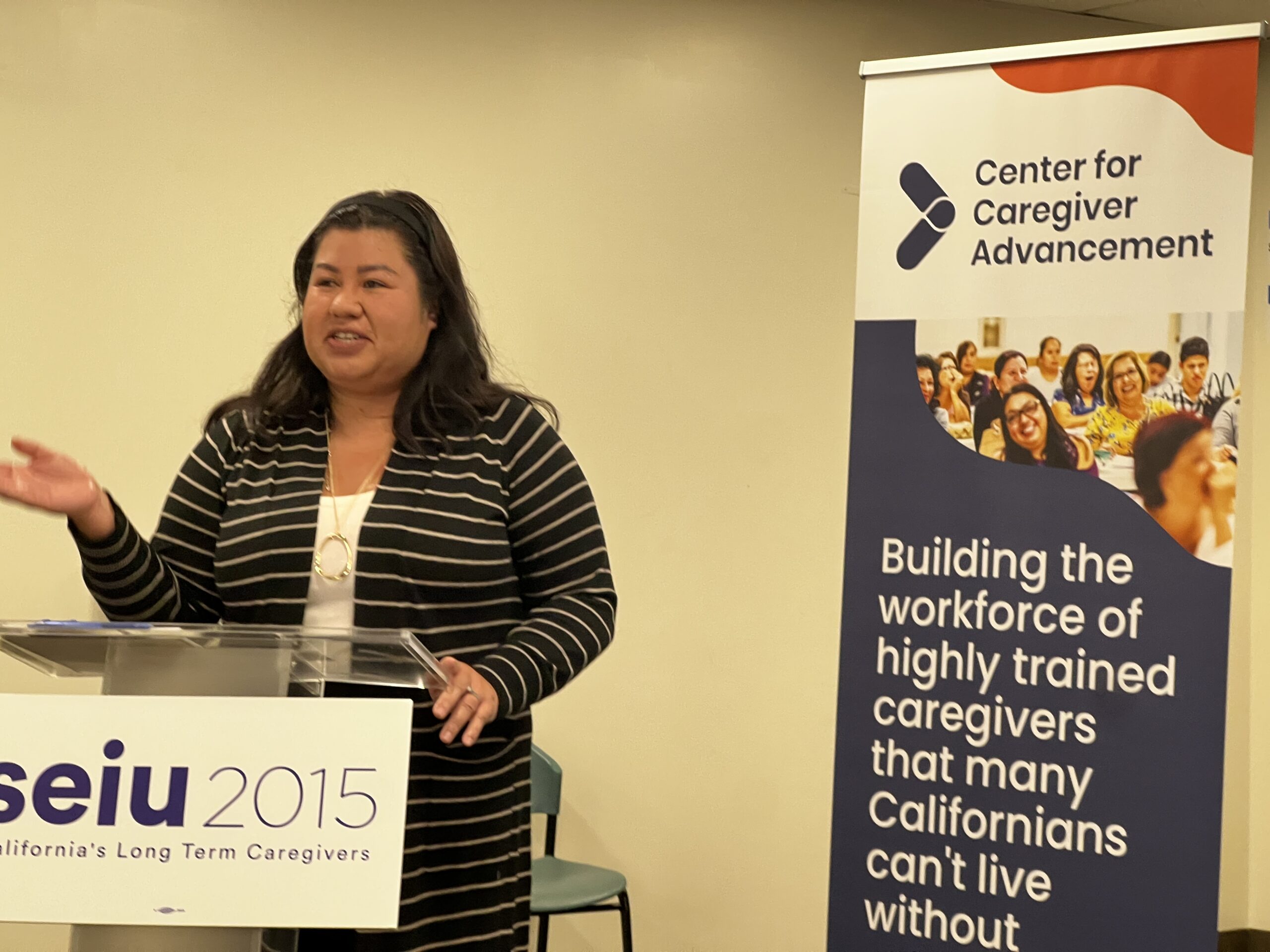

For that skill, Carlos credits the information he learned in the IHSS+ Alzheimer’s training for caregivers program. This program focuses on providing skills to people taking care of those showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. The program is offered by the Center for Caregiver Advancement (CCA) in partnership with the California Department of Public Health, UC San Francisco, and Alameda Alliance for Health.

As an In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) provider, Carlos already had been taking care of his mother for 10 years before he discovered the training. He had taken her into his home after she started exhibiting symptoms of Alzheimer’s in her late 50s. She is now 76.

“I took my mother to live with me not knowing what I was up against,” Carlos said. “In the beginning, she was able to do everything. She could go to the fridge and get lettuce and tomatoes. Now she doesn’t recognize what a fridge is, what a tomato is, so I have to work through that process.”

Even though he had a lot of experience being a caregiver by the time he took the training, Carlos said the specialized program for people caring for adults with Alzheimer’s disease was very useful.

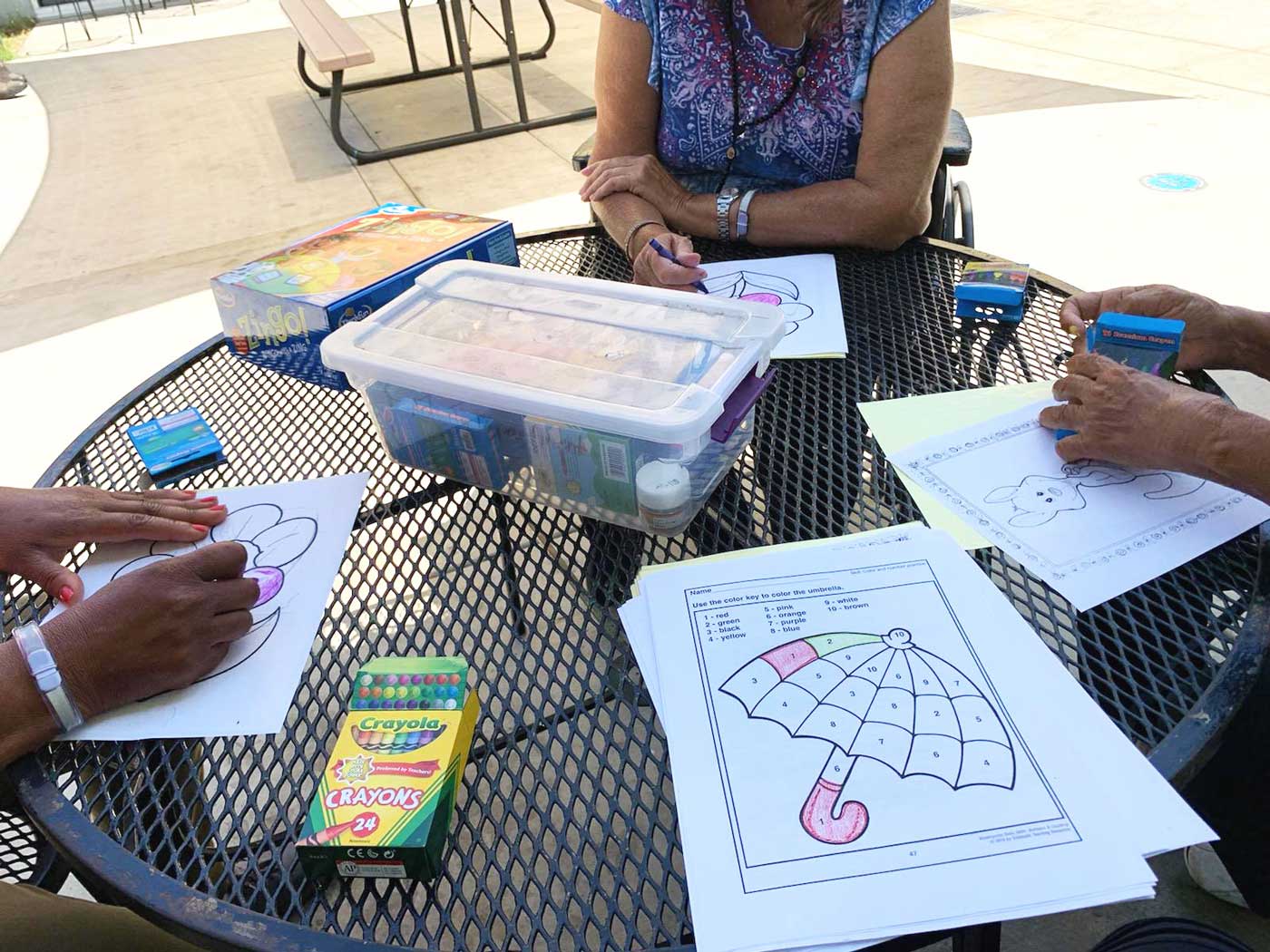

During the 10-week, 35-hour program, participants learn more about the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, how to manage hallucinations and repetitive behaviors, assist with personal hygiene, prevent wandering, reduce caregiver stress and avoid burnout. Caregivers also undergo CPR certification training and receive a stipend at the end of the program.

“One thing that impacted me which I never thought about until I took this course is (that) my elderly mother with Alzheimer’s remembers me in the past and not in the present,” Carlos said. “Because I am with her on a daily basis, I took it for granted that she knew who I was. But she only recognizes the son she had 10, 15 years ago and she doesn’t recognize my face today, and that never occurred to me. She doesn’t recognize my face. That’s the thing that impacts me the most.”

That realization prompts him to be more patient today, and not insist on doing things his way, Carlos said.

“With the training, I had come to more acceptance, that my mother doesn’t have the capacity anymore,” he said. “I can be more tolerant, or I can utilize different approaches to actually help her accomplish the same thing (like when she eats) because everything is regulated around her well-being.”

In the past, Carlos said he would walk away and leave his mother when she got agitated. Now, he stays and redirects the conversation from anger and hostility to calm and peace.

“I talk to her about her life before dementia and she kind of gets engaged in that,” he said.

It is bittersweet that as the disease progresses, his mother only remembers life from about the 1950s to 2000.

“I have to go back in time,” he said. “Everything beyond that is cut off.”

He will repeat instructions and questions, hoping something will make sense for his mother. She is still mobile and able to walk. But Alzheimer’s has brought her panic attacks and anxiety, which is now managed with medication.

Carlos said caring for someone struggling with Alzheimer’s is like trying to fit a key into a keyhole in the dark.

“You keep trying,” he said. “Before she goes to sleep, I gotta take her to the bathroom. She says, “Yes, I do want to go to the bathroom.” But once we get to the bathroom, she forgets. So we come out again. And we do that about three or four times and one of those times, she’ll remember. So we have to keep doing it, hoping that one of those times, it will click.”

The pandemic put a stop to the activities that got mother and son out of the house, and Carlos said he has learned to do more exercises with her.

“If my mother didn’t have Alzheimer’s she would probably outlive us all,” he said. “She doesn’t have high cholesterol, she has no diabetes, none of that. She doesn’t need any medication for her lungs or heart or kidneys. It’s just the brain, you know. Right now, she has a hard time trying to pull up the words when she’s willing to communicate with me.”

But her son does find words to describe his life and role as a caregiver. He said it is a choice and a commitment.

“Being a caregiver is a very noble profession,” he said. “I don’t think we quite grasp it, how much good we do. You need to be proud that you’re doing what you’re doing because not everyone is willing to do it. That’s how you give back to humanity, this is how you make a difference.”

Carlos said he gets help from one of his three siblings, one weekend out of the month. Otherwise, it is up to him to give his mother compassionate and dignified care.

“The best part of my day is when my mother is comfortable,” he said. “When you can see that she’s happy. You know that she ate well, she slept well. She’s clean. She took her shower, or she let me give her a shower without any resistance. And we’re on the couch and she’s watching TV, and she’s kind of engaging the TV. You don’t see any anxiety on her face. No panic. That’s probably my daily reward. I think that would be the best time.”